Our Reverse Migration - Part 10: Atlanta, GA

Loud Love, Nonviolent Roads, and the Architecture of Home

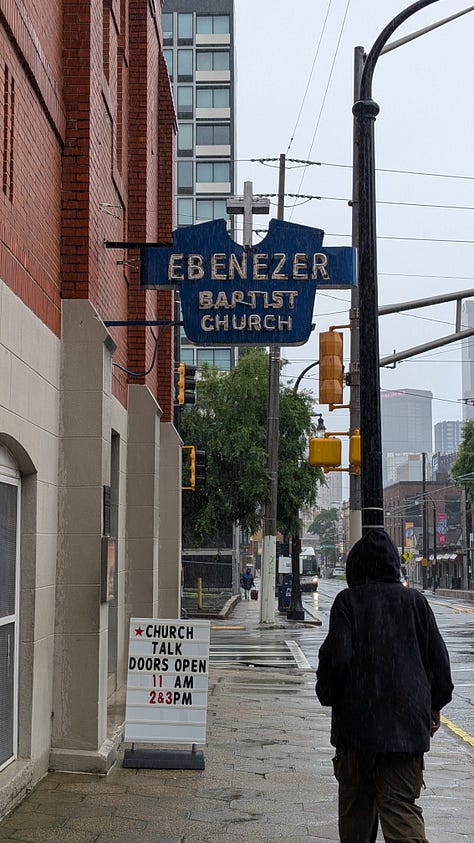

Visiting Atlanta brought up a lot—especially around Dr. King’s legacy and our ongoing reflection on violence and peace. Some of the details shared at Ebenezer Baptist Church were new to us—like how Dr. King’s mother was killed by a Black man who believed churches weren’t doing enough. That complicated truth reminded us again how violence can emerge from disillusionment, even within our own communities.

Being at Ebenezer, just days after standing at the site of Dr. King’s assassination in Memphis, felt like a full-circle moment. We couldn’t help but wonder: did he drive these roads? Was he making the same kind of pilgrimage we’re on now? He’s remembered as a nonviolent leader, but even he bought a gun toward the end—for protection. He knew he was going to die. That sense of foreboding, of impending sacrifice, followed us as we stood on the sacred ground where he once preached.

It’s wild—and heartbreaking—to consider how much effort our government put into tracking and targeting him. Surveillance, wiretaps, intimidation—all for a man whose vision was simply equality. We were struck by the irony that many white women, who have historically been complicit in the violence against Black men, are now beneficiaries of the very rights won through the Civil Rights Movement. We noticed how many white tourists were present at the church that day—many with European accents—which reminded us how deeply the world looks to Black America for truth and transformation.

That morning, Erin’s childhood family friend, Auntie Nissa, said something simple but profound: “Man God… are you Black?” It echoed something we’ve been feeling—that to suffer, to endure, to fight for dignity—often draws people closer to the divine. It reminded us of the book The Shack, where God appears as a Black woman—an image that rattled conservative churches but resonated deeply with people familiar with suffering.

Atlanta also reconnected us with personal memories. Staying with the Griffin family was like coming home. Despite all the harm I (Erin) experienced at Family Harvest Church (FHC), the Griffins were a joyful exception. They never diminished me—my voice, my womanhood, my Blackness. Their love, their laughter, the worship music in their home, the way they made breakfast—it all reminded me of how I grew up. It made me want to recreate that kind of love wherever we are.

This trip was also the first time I felt like we tangibly brought peace to someone else. The way the Griffins received us reminded them of the Matthew 10 passage: when you enter a home, bring your peace. And if your peace is not received, let it return to you. That’s what we’re trying to live out.

Community kept coming up for us, too. Being with people who know your story, who remind you who you are—that’s the grounding we need as we settle in Durham. We’re not just looking for collaborators—we’re looking for companions. People who want to bike, go to the movies, have deep conversations, or even watch One Piece. Because joy, laughter, and shared interests are part of peace work too.

We also spent a lot of time talking about violence—not just physical violence, but the structural, spiritual, and emotional kind. What does it mean to be peacemakers, not in a passive way, but in the deeply active, nonviolent tradition of Dr. King, Howard Thurman, and Gandhi? Gandhi’s concept of ahimsa—a way of life rather than a tactic—feels especially relevant now. It’s not just the absence of harm; it’s the presence of love.

We were reminded again how much King’s ministry threatened power structures. As soon as he began advocating for the poor and organizing the Poor People’s Campaign, they labeled him a communist. That’s how threatening it is when someone starts loving people radically.

The man who gave the talk at Ebenezer mentioned how Dr. King grew up in a neighborhood that felt like a version of Black Wall Street—a place where rich and poor Black folks lived side by side. That struck us deeply. It’s exactly what we dream of in Hayti—a neighborhood where everyone can live and thrive together, where economic diversity doesn’t mean displacement, but shared flourishing.

Atlanta gave us a lot to carry—memories of our past, hope for our future, and a deeper commitment to be people of peace in a world addicted to violence. It’s preparing us for what’s ahead. Including Rome.

We’re learning the walk of peace is not always quiet. Sometimes, it’s loud with laughter. Sometimes, it’s fierce with truth. But always, it’s rooted in love.