Our Reverse Migration- Part 7: New Orleans

How a City Preserves Its Soul and Culture Refuses to Die

Our time in New Orleans stirred something deep in both of us. As we continue this pilgrimage of reverse migration, this stop felt less like a visit and more like a remembering. We’ve always known New Orleans held a lot—but being here made it all click. As one of the original ports of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, New Orleans has found ways to preserve and honor its layered, complex history—especially the Black history that shaped it.

To explore more deeply, we took a tour with 2nd Line Tours, founded by Dennis M., also known as “The Katrina Man.” Since 2017, Dennis has been offering what he calls red-carpet rides through the soul of the city. But this isn’t your average tour—it’s a guided journey through the real New Orleans, unapologetically rooted in Black culture, memory, and resistance.

As shared on their website:

“I wanted to create a tour company that people from all parts of the world would be able to relate to. We are a company that’s not afraid to tell the true history of New Orleans. No other city tour bus company goes in depth about the Black experience like 2nd Line Tours does. We cover the Black Mardi Gras Indians, slave rebellions, second line funerals, the Civil Rights Movement, Baby Dolls culture, Congo Square being the birthplace of jazz, and much, much more. And along the way, we spotlight other Black-owned businesses, restaurants, and historical landmarks. 2nd Line Tours is my opportunity to give back to a city that has given so much to me. This is my home—and everything I am is because of what I have experienced and learned right here in New Orleans.”

It did not disappoint. If you're ever in New Orleans, this tour is an absolute must.

One of the most powerful stops on the tour was McDonogh 19 Elementary School, where three brave young Black girls—including Dr. Leona Tate—helped integrate the school system in Louisiana following Brown v. Board of Education. To our amazement, Dr. Tate herself was there. She now owns the building and has transformed it into a museum to preserve this critical history. I could hardly believe we were seeing her in the flesh. She was so kind, so gracious—and in her face, her haircut, even her spirit, I saw my Granny, Christine Willie. It was deeply moving.

As if that wasn’t enough, we happened to visit on NOLA Give Day—and the neighborhood was celebrating with a seafood boil. Kendall swears it was the best crawfish he’s ever had (and I agree!). Even the green beans that soaked in the boil were out of this world—I don’t even know how they made green beans taste that good. Like… what?!

One of the locals on the tour—a beautiful Black woman originally from New Orleans—had traveled the world and even lived in Senegal, only to return home. She spoke of New Orleans with such pride: so much to do, so much culture to experience, and so many incredible places to eat. We tried to get into the historic Dooky Chase Restaurant, but they were fully booked until the next day—and we’d already be gone.

She smiled and said, “Honestly, there are places even better than Dooky Chase”—her words, not ours. She recommended Neyow’s Creole Cafe, and wow… 10/10. Kendall got the chargrilled oysters—some of the best he’s ever had. I ordered red beans and rice, fried chicken, and a side of spicy sausage. Truly some of the best food I’ve ever eaten.

Something sacred is happening in New Orleans. Sometimes called the Black Hollywood, this city pulses with memory, resistance, joy, and spirit. We’re already dreaming about coming back—maybe with family next time. There’s still so much more to see, taste, and honor.

We came curious and left contemplative. One of the first things that struck us was learning about the German Coast Uprising of 1811—one of the largest acts of resistance by enslaved Africans in U.S. history. How is it that so few of us know this story? And how many other stories of resistance, revolt, and revolution have been buried in the soil of the South?

It reminded us that New Orleans holds a long memory. A sacred memory. One that finds ways to celebrate survival—loudly, boldly, and beautifully.

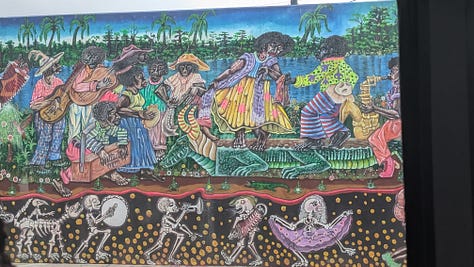

What stood out to us is how people in New Orleans stitch together wardrobes of resistance—clothes that carry messages, symbols, and stories. And whichever one is the most beautiful? That one wins. There’s something profound in that. It’s like beauty itself becomes a way to survive. The city celebrates everything—and that’s not just about fun; it’s about survival. They celebrate small things, every week, and in doing so, they reclaim something that oppression tries to take: joy.

We want to make sure our project, The Land Speaks, includes that same spirit of celebration. Maybe we even need to use the word “celebratory” when describing it. Because the African American story isn’t only one of trauma—it’s one of joy, resistance, creativity, and community. Especially when your back is against the wall, you make something beautiful anyway. That’s the story we want to tell.

There was also something deeply powerful in how Voodoo honors the sacredness of trees—as portals between the heavens, the underworld, and the world we live in. It made us pause and wonder about the mystics, the prophets, and our own traditions. What would it mean for us to truly see nature as sacred again? To honor trees, land, and the stories they hold?

We met up with Carl Webb from Durham on Zoom while we were there, and something he said has stuck with us: “There’s a sickness here.” He didn’t mean it in a judgmental way. He meant that trauma, hopelessness, and systemic injustice have left a weight on this place. A weariness. A kind of spiritual illness.

And then we remembered the story our tour guide shared: how enslaved people who ran away were diagnosed with a medical condition—drapetomania—a so-called sickness for simply wanting to be free. Imagine that. To desire dignity, autonomy, and liberation was once pathologized. Labeled as irrational. Dangerous. Sick.

It made us reflect on how those in power always find ways to name resistance as illness and conformity as health. But what if the sickness isn’t in the ones running, but in the systems they’re trying to escape? What if longing to be free is actually the most human thing of all?

New Orleans carries that tension. The weight of injustice is still visible—the Ninth Ward is still redlined, still under-resourced, and still grieving. Many locals believe, with good reason, that during Katrina, the levee was intentionally broken on the poorer side of the city to protect the wealthier parts. It’s happened before. There’s documentation of it happening in the 1920s—but this time, there was no warning. Just silence. And flood.

Anger, in that context, feels like a proper response. And yet—this city still dances. Still sings. Still cooks. Still preserves. And that preservation is what moved us the most.

New Orleans doesn’t just preserve its buildings—it preserves its soul. It preserves culture in ways that are still in use. You can still eat at the same restaurants. Still walk through the same neighborhoods. Still participate in the same rituals and traditions. Nothing is cordoned off behind glass. It’s lived. Practiced. Passed down. Alive.

It made us think of our own work—not just as community developers, but as preservationists. What does it mean to preserve culture in ways that keep it alive? That honor the past while inviting the present into it? How do we, like New Orleans, choose to love our culture loudly, with reverence and joy?

Our tour guide embodied that love. He was telling a living story. His reverence reminded us how rarely African American culture is celebrated so openly and unapologetically in public life. And yet here, in this city, it was vibrant. Centered. Whole.

We’ve been talking a lot lately about our own healing—how we had to find peace for ourselves before we could help others find theirs. And maybe that’s what we carry to Durham. Not answers. But a way of being. A story of how we got our hope back. A story we’re still writing.

New Orleans reminded us: we don’t just inherit the trauma. We inherit the creativity, the resilience, the rhythm, the beauty. And that’s worth preserving, too.